KC Column: 666

When I first started working at DC Comics, they were still in their legendary offices at 666 First Ave. in NYC. The offices were legendary because A) They were at 666 Fifth Ave. in a building with a giant “666” in bright red neon at the top of the building. This wasn’t too exciting in the daylight, but at night, seeing a giant “666” in flaming red neon made you think twice about a lot of things. B) By the time I got there, the offices were already past their capacity – yet they were still adding people. When Piranha Press editor Mark Nevelow moved into the building, they put him in a modified closet. When Archie Goodwin came over from Marvel, he had to share a conference room – as well as the conference table – with 4 other staffers. Close quarters doesn’t begin to describe how crowded it was. C) Remember the bright yellow polka-dot borders in the original Who’s Who in the DC Universe? That was the color of the wallpaper in the hallways at DC. Really. They really needed bright wallpaper in the hallways, because otherwise they were pretty dark, unless everybody’s office doors were open. But the yellow was so intense that if you stayed out in the halls too long, your eyeballs would start to vibrate. I once thought that maybe the yellow wallpaper was some sort of deterrent to keep people from congregating in the halls instead of working. Didn’t work – people were always in the halls. The offices were too crowded.

When I first started working at DC Comics, they were still in their legendary offices at 666 First Ave. in NYC. The offices were legendary because A) They were at 666 Fifth Ave. in a building with a giant “666” in bright red neon at the top of the building. This wasn’t too exciting in the daylight, but at night, seeing a giant “666” in flaming red neon made you think twice about a lot of things. B) By the time I got there, the offices were already past their capacity – yet they were still adding people. When Piranha Press editor Mark Nevelow moved into the building, they put him in a modified closet. When Archie Goodwin came over from Marvel, he had to share a conference room – as well as the conference table – with 4 other staffers. Close quarters doesn’t begin to describe how crowded it was. C) Remember the bright yellow polka-dot borders in the original Who’s Who in the DC Universe? That was the color of the wallpaper in the hallways at DC. Really. They really needed bright wallpaper in the hallways, because otherwise they were pretty dark, unless everybody’s office doors were open. But the yellow was so intense that if you stayed out in the halls too long, your eyeballs would start to vibrate. I once thought that maybe the yellow wallpaper was some sort of deterrent to keep people from congregating in the halls instead of working. Didn’t work – people were always in the halls. The offices were too crowded.

IT BEGINS

I started work at DC Comics at 666 in the summer of 1989. I’d been to the office a couple of times before that, however. My first visit there (actually my first trip to NYC, I think) was in 1983 while I was working for Capital City Distribution, and I was traveling with the co-owners of the company, Milton Griepp and John Davis. The three of us were in the back of a NYC cab when, out of nowhere, we were hit by another taxi cab. It wasn’t a bad accident, but we were shook up a little bit. Our cab driver, rather than check to see if we were okay, instead jumped out of the cab and ran to the other cab, pulled the driver out of the cab and started screaming at him. The second driver screamed back. I think there were some punches thrown, but I don’t recall any of them landing. All I really remember was sitting, dazed, in the back of this cab, when John turned to me and said, “Welcome to New York City!”

Later in the DC offices, we met Karen Berger for the first time. She had just become the new editor on the Saga of the Swamp Thing book. The first couple of issues by new writer Alan Moore had come out, and Karen was interested in our opinions. One of the guys (who obviously hadn’t read the books yet) kept talking about how awful and miserable the book’s sales were (which they were, pre-Moore, and probably for the first couple of Moore issues, until people caught on), but his negative assessment seemed to confuse her. At that point, we got yanked out of the room to meet with Paul Levitz or Bruce Bristow (then DC’s Marketing Director). As we were leaving, I quickly tried to tell her that I had read the books and thought that they were really great, but I’m not sure she heard me.

Later in the DC offices, we met Karen Berger for the first time. She had just become the new editor on the Saga of the Swamp Thing book. The first couple of issues by new writer Alan Moore had come out, and Karen was interested in our opinions. One of the guys (who obviously hadn’t read the books yet) kept talking about how awful and miserable the book’s sales were (which they were, pre-Moore, and probably for the first couple of Moore issues, until people caught on), but his negative assessment seemed to confuse her. At that point, we got yanked out of the room to meet with Paul Levitz or Bruce Bristow (then DC’s Marketing Director). As we were leaving, I quickly tried to tell her that I had read the books and thought that they were really great, but I’m not sure she heard me.

My other notable trip to DC was my actual job interview for what would become DC’s first creator-friendly (kinda) line, Piranha Press. There were a lot of other comics notables at the time being interviewed for the job, including Amazing Heroes editor Kevin Dooley, and I want to say Mark Waid and Brian Augustyn, but they may have already been at DC by then. Anyway, none of us “regular” comics guys got the job (no surprise, actually) – it went to Mark Nevelow, one of Jenette Kahn’s contacts – but the legend goes that everyone who was interviewed for that job ended up working for DC within a year or so anyway.

The interview was one of the worst performances in my life. Things went badly before I even got in the room, as I had almost passed out from low blood sugar (from not eating lunch) in Peggy May’s office about an hour before my interview. (Peggy was my DC Marketing/Press contact during my earliest years of writing for Westfield, and one of my favorite people in comics.) She very thoughtfully came up with some orange juice and cookies for me, patted me on the head, and sent me on my way. Thanks, Peggy!

All the interviews were in Jenette Kahn’s office, with both Paul Levitz and Dick Giordano in attendance. At least I think it was those three – my interview was very late in the day, and the afternoon sun was blindingly bright, so I was basically facing three silhouettes. As if I wasn’t already nervous enough, not being able to make eye contact with anyone was awful. I completely froze on the easy question – What are some of your favorite comics? – completely and totally blanking out. Later, after calming down slightly, I tanked the interview while they were explaining some of the nuts and bolts of how the new imprint was going to work. Someone had mentioned something about how DC would retain most of the rights to what was going to be published, and I jumped in and said something like “Well, that’s not going to work.” At the time in the industry, creator rights was a major issue, and the right to own and control your character was being asked for – and given – by most of the major indy publishers of the time. If DC wasn’t going to offer the same kind of creator rights being offered by the indy publishers, then they weren’t going to get any of the big-name guys they obviously wanted. So, I was basically telling the DC executives that they weren’t wearing any clothes – probably not the best move in a job interview. And obviously I didn’t get the job. But I ended up back at DC within several months anyway.

BACKSTORY

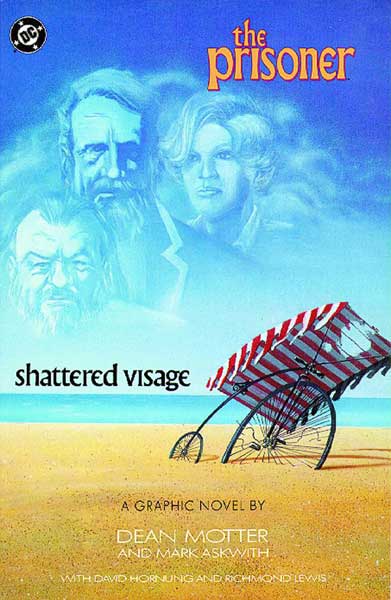

Richard Bruning needed an assistant. In 1989, Richard was doing what seemed like hundreds of jobs at DC under his title of Design Director, but at the core, he was the guy who made comic books look and feel important for the very first time. Not only was he instrumental in bringing a much-needed design sensibility to comics, he brought in actual graphic designers, worked with existing artists to improve their graphic sensibilities, and encouraged the use of artists who once would have never been considered for comics. Under Richard, DC experimented with formats, paper stocks, and printing techniques. Color – how it was done and how it was printed – became a priority for Richard. Projects that went through his fingers included Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, Camelot 3000, Ronin, Arkham Asylum, V For Vendetta, Baxter paper, Prestige format, DC’s early trade paperback collections, and dozens more, including the early Vertigo trade dress. Plus, he was editing a couple of projects, including Dean Motter’s sequel to The Prisoner, and writing Adam Strange on the side. He was a very busy man.

Richard Bruning needed an assistant. In 1989, Richard was doing what seemed like hundreds of jobs at DC under his title of Design Director, but at the core, he was the guy who made comic books look and feel important for the very first time. Not only was he instrumental in bringing a much-needed design sensibility to comics, he brought in actual graphic designers, worked with existing artists to improve their graphic sensibilities, and encouraged the use of artists who once would have never been considered for comics. Under Richard, DC experimented with formats, paper stocks, and printing techniques. Color – how it was done and how it was printed – became a priority for Richard. Projects that went through his fingers included Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, Camelot 3000, Ronin, Arkham Asylum, V For Vendetta, Baxter paper, Prestige format, DC’s early trade paperback collections, and dozens more, including the early Vertigo trade dress. Plus, he was editing a couple of projects, including Dean Motter’s sequel to The Prisoner, and writing Adam Strange on the side. He was a very busy man.

Richard and I had first met in Madison, when he was the editor for Capital Comics (the original publishers of Baron & Rude’s Nexus). At the time, Capital had folded – Nexus, Badger and Whisper were moving over to First Comics -and Richard had started planning his escape from Madison. But we hit it off before he left, having many intense conversations about comics and what they could be. Afterwards, we became phone buddies for a number of years, him talking about new things at DC and me keeping him up-to-date about the weirdness that is always Madison. One day in mid-1989, he called me and said “I need help. Get out here!” And so I went. Exciting things were happening.

Once at DC, I found myself assisting Richard doing basically everything and anything that needed doing. He was instrumental in teaching me the ropes about comic book editing, and my first assignments as an Assistant Editor were The Prisoner and a 2-issue Deadman mini by Mike Baron and Kelley Jones. Editing Baron was a challenge, as his “scripts” were actually thumbnails (with stick figures) indicating the general layout and positioning of the characters. Dialog was handwritten as balloons, or in the margins with arrows to indicate placement. It was my first opportunity to realize that every writer does things a little bit different from what you might expect.

The other major thing that I was supposed to do was log in and keep track of all the original artwork that came through Richard’s office. The logging in part was abandoned pretty quickly because it was done on Richard’s computer and as he was always sitting in front of it, it was just easier to for him to keep the log. And, hard as it is to believe now, this was before we actually had file sharing capability. I still assisted in keeping track of and protecting the original art, which was occasionally a challenge with large pieces like Dave McKean’s paintings. Often it was matter of finding a place to store the oversized packing boxes and crates that the artwork was shipped in – a challenge in the overcramped offices at 666.

Richard also taught me a lot about quality control in checking film for flaws, something that came in handy later when I became responsible for DC’s growing number of trade paperback collections. Little did I know that all of the quality control training was to set me up as one of the few people qualified to go to Montreal to do press checks at the printers there.

NO SLEEP AT MONTREAL

Press checks were done on DC’s most important books at that time, things like Arkham Asylum and all of the trade paperback collections. There was a lot of work to do once you were at the printers – checking dummy books to make sure the film was stripped up properly and all the pages were in order, and checking the actual film to make sure that requested corrections had actually been made. But there was also a lot of waiting around, mostly at night, when most of the comics were printed. What we were waiting for was the book in question to actually make it onto the press.

Press checks were done on DC’s most important books at that time, things like Arkham Asylum and all of the trade paperback collections. There was a lot of work to do once you were at the printers – checking dummy books to make sure the film was stripped up properly and all the pages were in order, and checking the actual film to make sure that requested corrections had actually been made. But there was also a lot of waiting around, mostly at night, when most of the comics were printed. What we were waiting for was the book in question to actually make it onto the press.

Once that happened, the presses would start rolling, and an early proof was pulled and given to me to check if everything was all right. And here’s where the fun began, as there wasn’t much time to check things as the presses kept rolling while you were checking! As the print runs on a lot of the early trade paperbacks were quite small, the total print time for a signature could be as little as 10 to 20 minutes. So, working as fast as possible, I had to check the proof against the dummy book to make sure all the pages were still in the right order as well as checking to see if the color levels were all correct. This was extremely hard to do because it was impossible to check everything, so I learned quickly some key things to look for: First and foremost was the quality of the black plate, which meant spot-checking the lettering, panel borders, and large black areas for blotching or fades (usually not a problem at Ronald’s as they ran a 5-color press and used the “fifth” color to back-up the blacks – but then you had to watch that the registration was true). For colors, I used to focus to make sure skin tones were correct. Beyond that, I watched for costume colors – Superman was easy to watch for as he was all red, yellow, and blue – the basic printing colors. The printers could make changes to the colors while the press was running – this is why the printed colors sometimes vary from book to book – but stopping the presses for anything was always a last resort, although it could be done if something catastrophically wrong, like pages out-of-order or occasionally missing or blank.

Ronald’s generally was a very good printer – much better than the traditional Sparta, Illinois, comics printer, especially after they switched to the dreaded Flexographic printing – but they were a high-speed printer, not really one set up to do “art” quality projects. Thus, it was always tricky when an artist or colorist wanted to attend a press check, as happened when David Lloyd accompanied me for the first V for Vendetta trade paperback. David’s original coloring for the work was amazing and subtle, and he spent a lot of time on press trying to get everything perfect, but taking too long to get there. So the books on the tail end of the print run looked very nice, but the colors varied wildly throughout the rest of the run. Unfortunately, by the luck of the draw, Dave’s creator copies came from the front of the print run, before the colors were adjusted to Dave’s liking, and he was, understandably, not happy with them. Fortunately, there were much better printings of the book to come!

The tedious part of press checks was the waiting between the press runs. After a signature was printed, the press was stopped, cleaned, and then set up for the next signature. Often this took up to an hour to accomplish, so there was nothing to do but wait. Ronald’s had a waiting room just for this, with TV and VCR, but all they had to watch was Dirty Harry movies. Usually, I just tried to catch a quick nap before the next run.

Occasionally, something would go wrong, and the presses would be down for hours. In cases like that, Ronald’s would put us up in a hotel so we could get some real sleep. After one press failure, I was deposited – at 4 in the morning – at a five-star hotel in downtown Montreal, in a suite in the top floor of the hotel. When I got to the room, all the lights were out and I couldn’t find any light switches. There was just enough light coming in from a window so I could sort of “feel” my way around the place, but I found myself going into what seemed like a dozen different rooms, none of them bedrooms, and none of them with accessible light switches. Exhausted, I flopped down on a couch and immediately fell asleep. When I awoke in the morning, the room was filled with sunlight, and I could see a hidden stairway that somehow I overlooked in the dark. It led to a gigantic bedroom. Nobody had told me it was a two-story suite.

BACK TO NYC

Living in New York City was a big change for me. It took me a long time to figure out the city. Even simple things were hard if you weren’t used to them. Two things I initially had trouble with in NYC were revolving doors and umbrellas. Growing up in Wisconsin, I had never really used either one.

Seemingly, every building in the city had a revolving door. And to use them properly, there is a secret nonverbal language that outsiders must learn or else have various limbs amputated on a regular basis. The stereotypical New Yorker is usually pictured as trudging up and down the concrete canyons, shoulders stooped, eyes staring at the pavement and making eye contact with absolutely nobody. It’s totally true. This, by the way, is direct opposition to the typical NYC tourist, who constantly walks around with their heads pointed skyward, as if they’re waiting for Superman to fly overhead. They don’t make eye contact either. But to use a revolving door properly, one must make eye contact – often grudgingly fleeting, embarrassed eye contact – or risk either killing someone else with the big, heavy, revolving glass door, or being killed by somebody else. Plus, there’s this weird little dance that’s a lot like Fight Club – no one talks about it. And God help you if you encounter tourists with children in a revolving door.

Seemingly, every building in the city had a revolving door. And to use them properly, there is a secret nonverbal language that outsiders must learn or else have various limbs amputated on a regular basis. The stereotypical New Yorker is usually pictured as trudging up and down the concrete canyons, shoulders stooped, eyes staring at the pavement and making eye contact with absolutely nobody. It’s totally true. This, by the way, is direct opposition to the typical NYC tourist, who constantly walks around with their heads pointed skyward, as if they’re waiting for Superman to fly overhead. They don’t make eye contact either. But to use a revolving door properly, one must make eye contact – often grudgingly fleeting, embarrassed eye contact – or risk either killing someone else with the big, heavy, revolving glass door, or being killed by somebody else. Plus, there’s this weird little dance that’s a lot like Fight Club – no one talks about it. And God help you if you encounter tourists with children in a revolving door.

Umbrellas are totally another story. The first thing that you learn about umbrellas in NYC is that you are a complete doofus if you wait until your first rainstorm to buy an umbrella, because suddenly, the umbrella you could have bought for $2 when it was dry costs somewhere between $20 and $1,000,000 when it’s raining. Further, buying an umbrella in NYC if you are a man is a daunting proposition, because it seems that the only places that sell umbrellas in Manhattan are women’s clothing shops – a place that men only go into when they’re dragged there. Apparently, having an umbrella is not a manly thing to have in NYC. Neither is pneumonia. So it’s an interesting choice to have to make.

Once you have the umbrella, one generally doesn’t think that it’s something that you need practice with, but you actually do, as there is usually some sort of super-secret release mechanism that’s impossible to find. After you start turning the closed umbrella over and over in your hands trying to find the button in the pouring rain, it will inevitably open up right in your face – usually with enough force to either knock you out cold or send your glasses flying into the street and crushed under the tires of an empty taxi that refuses to stop for you. I found that I had a great affinity for buying the cheap model umbrellas that often launched the open “brolly” section into the sky – with me still holding the handle. If there was a good stiff wind (as there always is in NYC rainstorms, what with the concrete canyons and all), the “brolly” would sometimes sail as much as 7 or 8 stories high. Just like flying a kite – without the string.

My DC “friends” were always quite amused by my inability to use an umbrella properly. “How do you not know how to use an umbrella?” they would ask, annoyingly, in unison. “In Wisconsin, we didn’t need umbrellas,” I would bellow. “We had cars!”

BACK TO 666

One of the first things I was taught to do at DC was forge Dick Giordano’s signature. If I recall correctly, there were a couple of people who did this. We never did it with anything too important, like checks or vouchers, but if there was anything annoyingly bureaucratic that we had to get done and needed Dick’s signature when he was out of the office, then someone forged his name. We just had to remember to tell Dick what we had done later.

Mike Gold’s bulletin board drove me nuts when I was at DC. Everybody else’s bulletin boards were a jumbled mess of cover sketches, notes, calendars, color guides, and what-have-you. Some folks competed to see how many cover sketches would stay attached with a single pushpin. Mike Gold’s bulletin boards were fastidiously neat. Everything on his board was lined up in rows, and every piece of paper was attached with four pushpins, one in each corner. There were dozens and dozens of pushpins on his board. I used to think that if DC ever went broke, the cause would be Mike Gold’s pushpins. One morning while I was in the area bothering Bob Greenberger, Bob started talking about Star Trek, and as usual, my eyes glazed over and focused on something else – Mike’s bulletin board. It was then I realized that not only was everything on it annoyingly neat, but that every sheet of paper had four pushpins of exactly the same color. That piece had four red pushpins. This one had four yellow pins. And so on.

Mike Gold’s bulletin board drove me nuts when I was at DC. Everybody else’s bulletin boards were a jumbled mess of cover sketches, notes, calendars, color guides, and what-have-you. Some folks competed to see how many cover sketches would stay attached with a single pushpin. Mike Gold’s bulletin boards were fastidiously neat. Everything on his board was lined up in rows, and every piece of paper was attached with four pushpins, one in each corner. There were dozens and dozens of pushpins on his board. I used to think that if DC ever went broke, the cause would be Mike Gold’s pushpins. One morning while I was in the area bothering Bob Greenberger, Bob started talking about Star Trek, and as usual, my eyes glazed over and focused on something else – Mike’s bulletin board. It was then I realized that not only was everything on it annoyingly neat, but that every sheet of paper had four pushpins of exactly the same color. That piece had four red pushpins. This one had four yellow pins. And so on.

“You see this?” I asked Bob.

“Yeah,” he said. “So what?”

“This must stop,” I replied, as I am the Chaos Bringer.

So one morning I got into the office early, which was tough because Mike also was an early arrival most mornings. I snuck into Mike’s office – and rearranged all the pushpins! It was absolute chaos. Blue pushpins were mingling with yellow pins, green pins were fraternizing with red. Some papers had (gasp!) four different color pushpins! Oh, the humanity!

I finished up, fiendishly cackled, and ran away and hid. A few minutes later, I saw Mike come in and head toward his office. I gave him a couple of minutes to take his coat off and get settled before I would come in on some bogus pretense and see if he would notice. Not more than two minutes had passed before I entered his office to watch what would happen.

The joke was on me. As I entered the office, my eyes darted directly to the bulletin board, expecting to see my dastardly work still in place. Instead, my eyes bulged open wide. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing! The board was back to the way that it started – with four pushpins of the same color holding up each piece of paper! How could this be? It took me at least five minutes to mess up the board. How could he restore it in less than two, much less notice it in the first place while also getting settled for the day?

I stammered some lame excuse about forgetting why I was there and backed quickly out of his office. Later, I came to the only conclusion that I could:

Mike Gold is not human.

I don’t know if he ever thought it was me that messed up his board. I was pretty quiet most of the time – thus I could easily get away with stuff like this. Perhaps as a non-human he was beneath such things. I guess he knows now.

My abhorrent behavior against neat freaks didn’t stop here, sadly. For over 20 years now, my pal (and former DC 666 denizen) Tammy Brown (and her Band of Renown) and I have been doing a similar little dance. Tammy always fastidiously cleans her home whenever I visit, including creating the (to me) pretentious “magazine spread on the coffee table” so popular in all the fashionable beautiful homes magazines. To me it’s like waving a red flag in front of a bull. As soon as I hit Tammy’s living room, I’m at the magazine spread with both hands, messing it up with great gusto and ending with a hand flourish and a “Perfect!” I just can’t help myself. After years of this, I asked her why she still bothered with the spread, knowing I was just going to mess it up, she answered dryly, “because if I didn’t, you’d just destroy the whole house!”

I’ve got lots more 666 stories. I haven’t even mentioned Dollar Beer Night. Or why it’s bad to play softball in Central Park after giving blood. Let me know if you’re interested in hearing more. (Or if you were there, correcting my increasingly faulty memory!)

PLUG-OLA

My old pal Mark Waid has just launched a new blog and forum over at BOOM! that everyone should check out. The blog is mostly about “Writing 101” – tips and stories about how it’s done from one of the best. Mark’s been just about everywhere, written about most everything and has faced more adversity (most of it not even of his own making) than just about anyone in the industry. And the forums are just plain fun! Go check it out at http://www.markwaid.com (which actually defaults to http://markwaid.boom-studios.net/).

KC CRLSN dn’t lk vwls nmr.

Got comments or questions about this column? You can contact KC at AuntieKC@WestfieldComics.com