KC Column – Creation Comforts 2

by KC Carlson

[This is a continuation of the exploration of character creation in comic books. Part one appears here. If you haven’t read that yet, you may want to. Then come back here for more.]

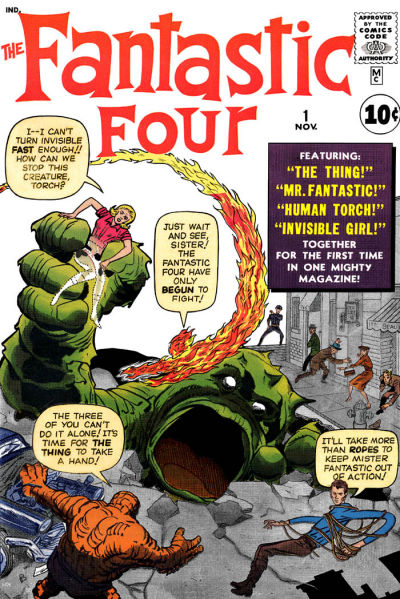

So far, most of my examples of character creation have been DC characters. There’s a reason for that. The folklore of the modern Marvel Universe suggests that most of the classic Silver Age Marvel characters were created by either Stan Lee and Jack Kirby or Stan with Steve Ditko. (Important, but occasionally forgotten exception: Captain America was created in the Golden Age by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby – not Kirby and Stan Lee.) Debate has literally raged for years as to which did more or who was more important, mostly along the lines of the writing vs. artwork conundrum. Chances are we’ll never know for sure, but things are about to get very interesting as the Kirby heirs are now taking certain claims to a court of law. Marvel’s new bosses may come in handy in the fight, because Disney’s lawyers define the concept of “high-powered” and have been warding off challengers to the Disney Way for decades. Woe to the Kirbys. But Jack was the epitome of the little guy standing up for himself against impossible odds, at least in the characters he drew. If he and Roz managed to bestow any of their moxie onto their kids, it could be one hell of a fight.

The Marvel Method

Part of the confusion about who did what can be attributed to a working style between collaborators favored by Lee (mostly because he was usually tasked with writing the bulk of the comics he was editing/producing during his long history with notoriously cheap publisher Martin Goodman). This came to be known colloquially as the “Marvel Style” of producing comic books. Prior to this, comics were usually produced by a writer writing a complete script (plot and dialogue, similar to a movie or TV script, except stage directions were largely embellished with the addition of panel breakdown instructions) and then that script was illustrated by the artist, lettered, then inked and colored.

Stan’s method featured a very loose plot, with no stage directions. This type of plot, when typed, usually only amounted to a page or two, giving just the rudimentary “beats” of the story to be told, and only skeletal dialog, if any at all. Occasionally, there would be no written plot at all. Stan would tell the artist the story beats in a face-to-face plotting session or via a telephone conversation. The artist would then be responsible for all the storytelling decisions – panel breakdowns, how many pages (or panels) to devote to each scene, and even what to emphasize in each panel/page. Some thrived under this system, which offered the creative artist much more control over the total “look” of the story. Others, used to working from a script which broke down much of their work for them, resented having to do more work for the same pay. (Eventually, standard page rates were adjusted for this kind of work.)

When the artist was through, the art was returned to the writer, who then wrote the actual dialog for the now penciled pages, which when finished, went directly to the letterer. Some artists, like Kirby, loved adding suggested dialogue in the page margins for the figures that they just drew. (Why not? They spent hours perfecting the characters’ faces. Why not daydream what the characters were saying?) This further blurred the line between the previously established creative roles of writers and artists, especially when the writers frequently used the artist’s suggestions – and got the credit for them as well!

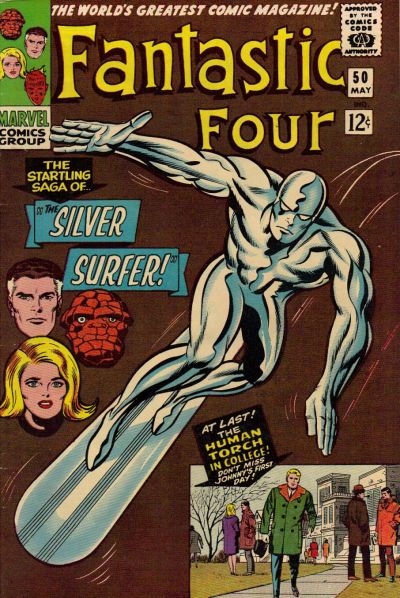

In at least one case, the “Marvel Style” led to a very interesting creator situation. When Stan Lee received the Jack Kirby-penciled pages back for Fantastic Four #48, Stan encountered something he hadn’t planned on – a new character whom he had never seen or discussed with Kirby. Or, in his own words, “There, in the middle of the story we had so carefully worked out, was a nut on some sort of flying surfboard.” (The Ultimate Silver Surfer [BerkeleyTrade, 1995]). Thus was born the Silver Surfer.

After hearing what Kirby had intended for the character, Lee was won over and started adding dialog and characterization to Kirby’s Koncept, and soon an important new character became part of the Marvel Universe. Ironically, Stan became very protective of the character, allowing no other writer to use him for many years afterwards. Writers Roy Thomas and Steve Englehart later wrote of the special permissions they had to get from Stan to include the Surfer in the Defenders and the “Titans Three” stories which preceded them. This is why the Surfer wasn’t a regular Defender in the early days of that series.

So, who created the Silver Surfer? I’m not touching that one with a 10-foot longboard. But someday soon, some poor judge is probably going to have to make that ruling.

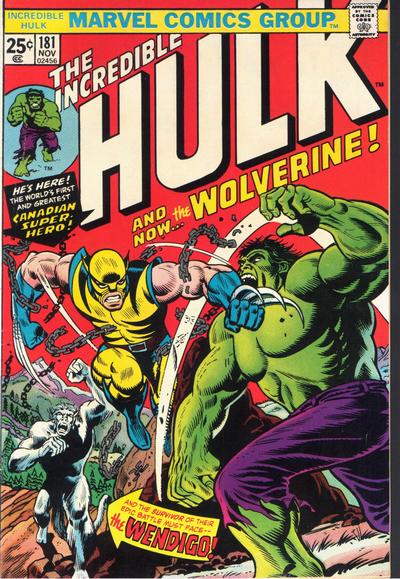

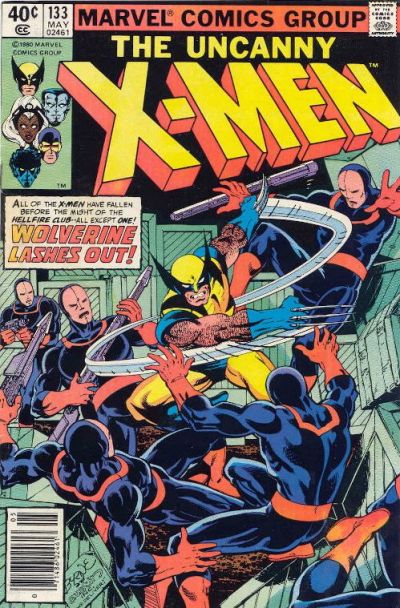

…What I Do Best Isn’t Very Pretty

The creation of Wolverine offers a neat little capsule history on how characters are created and built upon in the modern age of comics. Wolverine first appeared, in a one-panel cameo, in Incredible Hulk #180, before showing up in the following issue for a furious three-way battle with ol’ Greenskin and a beast that was called the Wendigo. This storyline – which also continues into Incredible Hulk #182 – was written by Len Wein and drawn by long-time Hulk artist Herb Trimpe. However, the character was famously designed by artist John Romita, Sr. Character design was part of Romita’s role as Marvel’s then-current art director, and Romita designed dozens of characters for Marvel over the years in this job. Marvel doesn’t generally publish creator credits in their comics, but all three of these gentlemen – Wein, Trimpe, and Romita Sr. – are usually credited as the creators of Wolverine. But the story doesn’t end there.

Roy Thomas also has claims to the character’s origins, at least from a pragmatic point of view. Then Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief, Thomas was presented with information that Marvel had a fairly large Canadian readership but no Canadian characters. So he came up with a couple of names and some basic details for the character (like animalistic traits) and discussed this with Wein during a plotting session for the Hulk story.

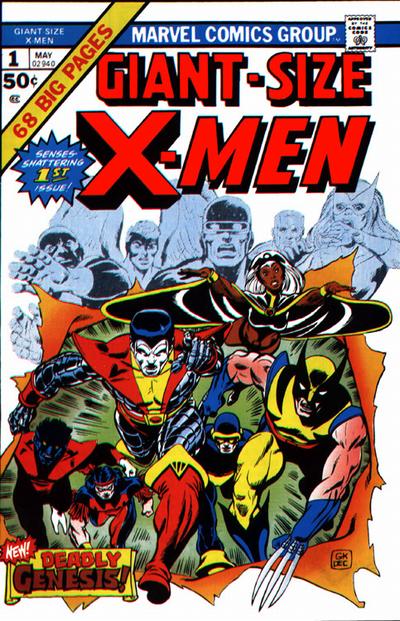

Wolverine’s next appearance is generally considered an even bigger deal than his first. He pops up in Giant Size X-Men #1 as a member of the all-new X-Men team, again written by Len Wein with art by Dave Cockrum. Cockrum designed several of the new characters after Thomas described the concept as “mutant Blackhawks”. Wolverine was a natural fit on a team made up of international characters. Wein left the series almost immediately (he was writing four other Marvel titles at the time), and Chris Claremont picked up the assignment, after unofficially contributing plot points to earlier X-Men issues.

At this point, Wolverine was still a cypher of a character. Both Claremont and Cockrum added much in the way of personality details to the Canucklehead, but not too much in the way of background to the character, something that would be an ongoing state of affairs for many years. Cockrum was the first artist to draw Wolverine out of costume, giving him his distinctive hairstyle. However, the character was not a favorite of Cockrum, who spent most of his run developing his favorite X-Man – Nightcrawler.

When Cockrum decided to take a Marvel staff job and stop drawing for a while, the next artist in took a big shine to Wolverine – most likely because they were both Canadian! When John Byrne signed on to the X-Men, things really began to happen for the team, as well as Wolverine. Byrne was a speed demon as a penciller, especially compared to the more methodical Cockrum, so the first thing that happened was the book went monthly!

(It’s hard to believe now, but for the first several years of Uncanny X-Men, the book was a risky, low-selling proposition for Marvel compared to the big guns like Amazing Spider-Man and Fantastic Four. It’s also hard to believe, but at first Byrne’s X-Men was hated – HATED! – by the hardcore fans who wrote letters crying that Byrne’s art was too “cartoony”. This is actually one of the first recorded instances of the hardcore letter-writers being out of step with the casual comics fans, who eventually bought the Byrne-drawn book in such quantities that it soon rocketed to the top of of the list of Marvel’s best-selling comics!)

Byrne also became more involved with story-related elements for the X-Men, especially where Wolverine was involved, and Claremont and Byrne wasted no time in adding more details (as well as more mystery) to the background of Wolverine, such as his enigmatic connection to the Canadian super-team Alpha Flight, some of whose members Byrne had created as a fan. Eventually, Byrne received a co-plotter credit on X-Men. He also messed around with Wolverine’s visuals for a bit and was responsible for toning down the bright yellow in his costume.

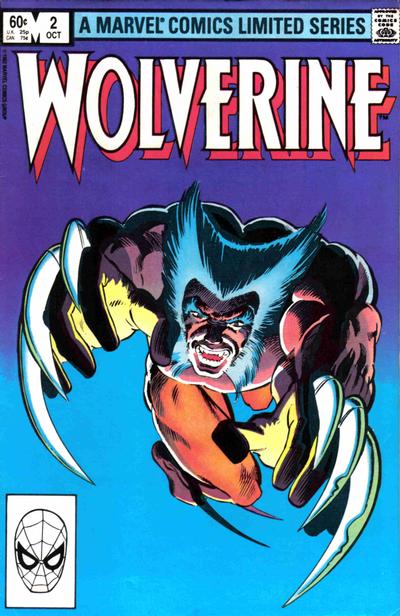

Later, Claremont and Frank Miller explored the character’s Asian connections and background in Wolverine, one of the first comic book miniseries. Throughout the years, various creators added bits and pieces to Wolverine’s past, indicating that he was probably much older than we believed when the character was first introduced. The character was present at various times in modern Marvel history, most notably during W.W.II, and he had been known by a raft of aliases and alternate identities including what we thought was his real name – Logan.

For years, fans and creators alike debated Wolverine’s actual origins. Was he a mutated wolverine with connections to the High Evolutionary? Was his arch-foe Sabertooth actually his father? And what about the mysterious Weapon X program, told in a revolutionary and memorable series by Barry Windsor-Smith?

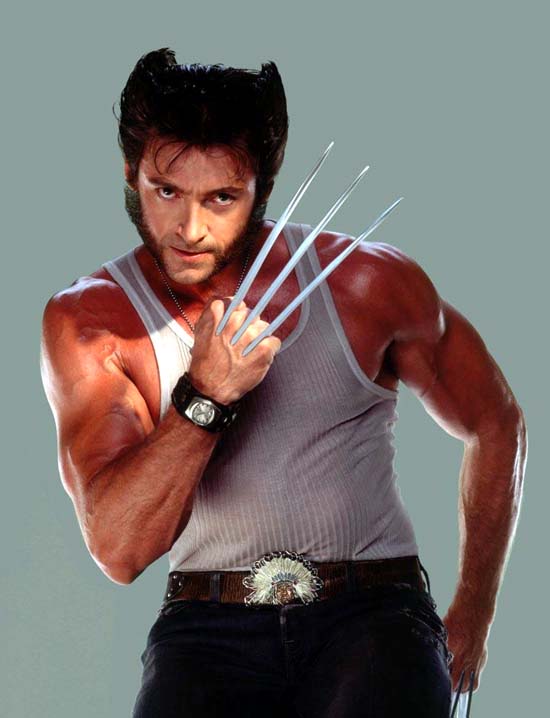

It’s hard to believe, but an actual honest-to-gosh origin story for Wolverine did not happen until over 25 years after his first appearance in Incredible Hulk. Origin was written by Paul Jenkins, Joe Quesada, and Bill Jemas and illustrated by Andy Kubert (pencils) and Richard Isanove (colors). It reveals how Wolverine came to be in a story set in late 19th century Canada. Apparently, the behind-the-scenes impetus for finally revealing Wolverine’s secrets came from the realization that now that he was a successful movie character (in the popular X-Men movie franchise), his origin should be told in the comic books – by comic book people – before the movies got to it first. The fourth movie in the film series – X-Men Origins: Wolverine – did a pretty fair job of adapting the comic.

So who created Wolverine? Obviously, Len Wein and Herb Trimpe produced the first story the character appeared in. But John Romita, Sr. and Roy Thomas also contributed behind-the-scenes. These days, that character bears little resemblance to the character who appears in at least three monthly comic books from Marvel. And where do people like Chris Claremont, John Byrne, and Barry Windsor-Smith – not to mention many others – fit into the bigger picture? What about Hugh Jackman, who wonderfully brought the character to life in the movies?

I think Wolverine had a lot of daddies!

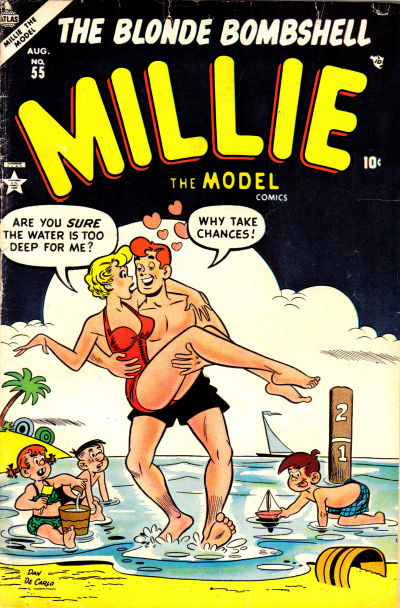

She’s Josie!

Not even basing your character on your wife is enough “proof” for a creatorship claim in the world of comics. Artist Dan DeCarlo’s work is probably some of the most recognized in comics, although not many people know who he is. DeCarlo was not often officially recognized for his art during his lifetime, despite working in comics for more than 60 years. Older fans recognize his work for Timely (Marvel) Comics starting in 1947, where he primarily drew humor titles and “girly” comics like Millie the Model and My Friend Irma. At first he went uncredited, but over his ten-year run on Millie, DeCarlo was allowed to sign his covers, and much of his interior work bore the by-line “by Stan and Dan,” Stan being none other than Stan Lee. Lee loved working with DeCarlo and was horrified when he had to let DeCarlo go during one of Timely’s frequent downsizings in the late 1950s. The two still worked on projects together over the next few years. Just not for Timely.

Back then, it was every comic artist’s dream to ultimately land a syndicated comic strip. And it was no different for Stan Lee and Dan DeCarlo, who worked together on a number of potential strip ideas, most of which were non-starters. One was a short-lived syndicated strip about a mail carrier named Willie Lumpkin. The strip didn’t survive (a few were reprinted in Marvel Age many, many years ago), but the character did. He became the Fantastic Four’s mailman in FF #11 (Feb. 1963) and has been a (minor) part of the Marvel Universe ever since. Prior to landing Willie Lumpkin, Stan and Dan also developed a strip based on two teenagers called Buzzy and Bunny. While this strip was in development, DeCarlo decided to change one of the supporting characters’ names from Lizzie to Josie, after his wife. Shortly after that, the real-life Josie came home with a stunning new hairstyle that inspired Dan to spin the newly designed Josie, with the same stunning style, into her own strip proposal. Unfortunately, neither Buzzy and Bunny or Josie sold to the syndicates, but Willie Lumpkin did, and so DeCarlo pushed the Josie concept to the side to work on Willie Lumpkin. For a while.

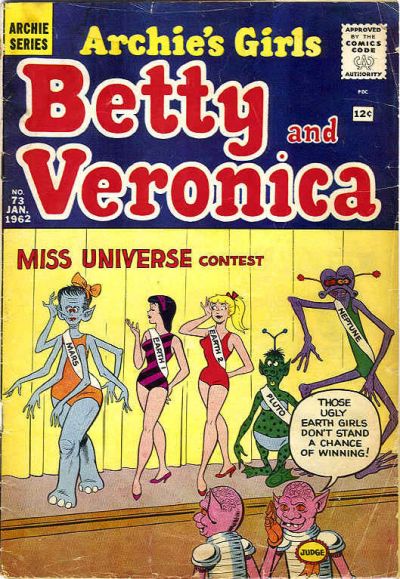

Since DeCarlo wasn’t exclusive to any company, he worked on a number of other humor comics for many other publishers in between his assignments for Timely. One of the companies he did freelance work for was Archie Comics. His earliest reported work for them appears in Archie’s Girls, Betty and Veronica #4 in 1951. He didn’t much like working for Archie in the beginning; they had among the worst pay rates in comics and, at least in those early years, he was constantly being told to draw like Archie artist Bob Montana. But he especially loved drawing the iconic blonde and brunette and managed to get at least a page or two in most early issues of the series.

Eventually, the Archie folks realized that the issues that had DeCarlo’s work sold better than those without, and DeCarlo was finally told that he could draw the characters the way he wanted to, without using the Montana reference. By 1957 or so, he was drawing almost every issue of Betty & Veronica, and by 1961 (after being laid off from Timely and the failure of Willie Lumpkin), he was pretty much full-time at Archie. In short order, he became “the” Archie artist for several decades, eventually drawing over 400 consecutive issues of Betty and Veronica (over two series), taking over the flagship Archie title in the 1970s (as well as the syndicated Archie comic strip), and becoming the regular (and ultimately iconic) cover artist of most of Archie’s entire line of comics. Ironically, by the late 1950s, other Archie artists were being told to draw more like Dan DeCarlo. DeCarlo is easily one of the most prolific artists in comics, matching or bettering the page counts of other industry giants such as Jack Kirby, Curt Swan, Warren Kremer (Harvey Comics), and Carl Barks.

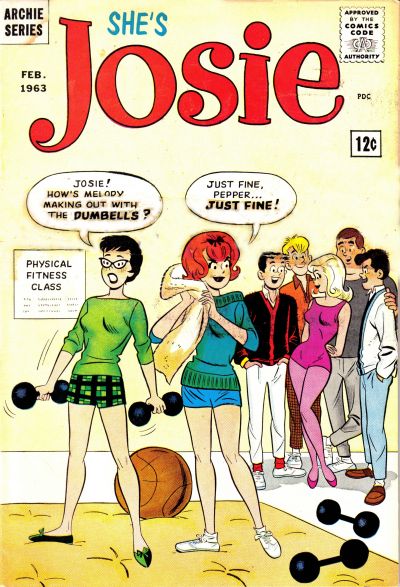

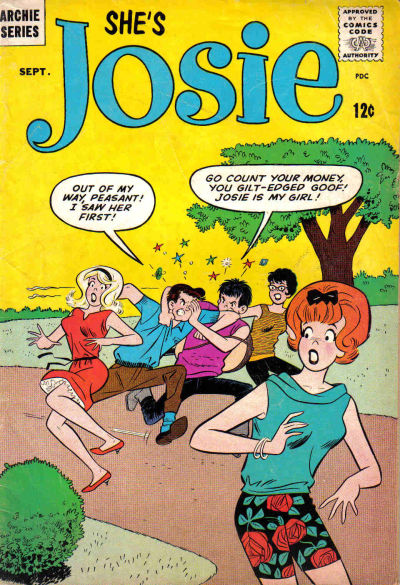

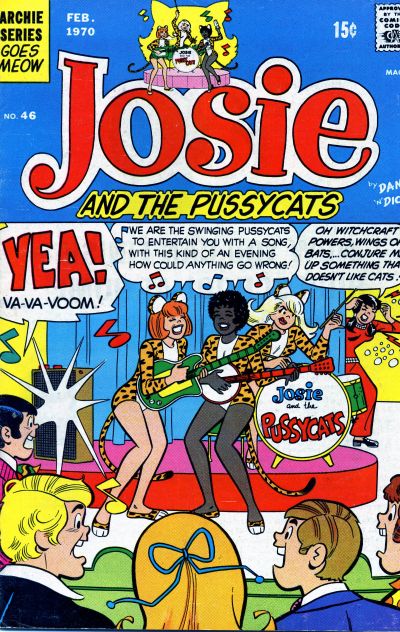

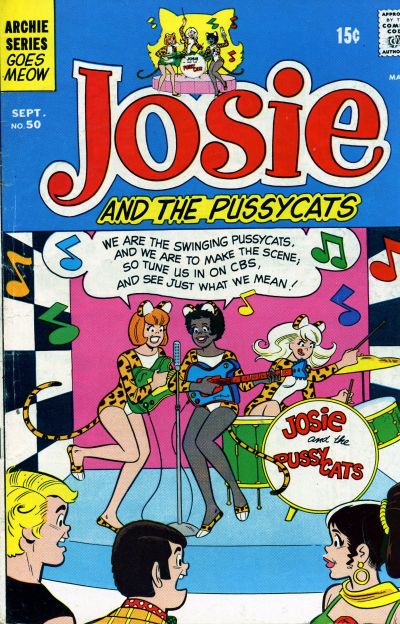

In the early 1960s, DeCarlo showed his earlier Josie syndicated strip proposal to Richard Goldwater, then an editor at Archie and the son of Archie Publisher John Goldwater. After getting both their approvals, DeCarlo was given the go-ahead to produce a comic series based on the Josie strip. She’s Josie debuted in 1963.

As true Josie fans know, the original cast of characters was different from the better-known 1970 CBS animated cartoon. Josie, of course, was the main character, along with ditzy blonde bombshell Melody and the stereotypical bookworm (she wore glasses) Pepper. Although based on broad stereotypes, these girls were fully formed characters in DeCarlo’s hands. The brunette Pepper had a slyly wicked sense of humor, and Melody amusingly had no idea of her effect on the male libido. Her speaking voice is also apparently very melodic, as her word balloons are filled with musical notes. The males included Albert (also from the aborted comic strip), who started off pretty boring and bland until he was sucked into virtually every sixties fad from folksinging to Beatles to hippyism, and Sock, short for Socrates, an ironic nickname as Sock was a near Neanderthal in intellect and style (think typical male slob sitcom character). He was actually very sweet and loved Pepper.

Also in the cast were the spoiled rich twins Alexander Cabot III and his sister Alexandra. Alex and Albert battled for the hand of fair Josie, in a gender-reversed Archie/Betty/Veronica conflict. Alexandra wasn’t really fully developed until the Pussycats days, where (in the comics at least) she developed a limited amount of magical abilities in conjunction with Sebastian, her cat and familiar. Until then, she basically lorded over Josie and Pepper and occasionally clashed with Josie for Albert’s attention. (Although it seemed that she didn’t really care for him that much, but just didn’t want Josie to have him.) This cast appeared in the Josie comic from 1963 to 1966, as well as appearing in a lone issue of Archie’s Pal’s and Gals #23 (ironically, the cast’s first appearance, just barely predating She’s Josie #1), as well as irregular appearances in both Pep Comics and Laugh Comics.

DeCarlo was uncredited in the early issues of Josie (as was the style of the period, where few comics creators received credit), but starting with issue #22 in 1966, the covers of the comics were adorned with the blurb “by Dan ‘N’ Dick” — Dick being Richard Goldwater. It’s always been kind of unclear exactly what Goldwater’s contribution to the Josie comic book was, but in one of his last interviews (The Comics Journal #229, Dec. 2000), DeCarlo indicated that after he showed Goldwater his original Josie newspaper strip ideas, they came back with the credit “by Dick and Dan” on the top of the strips. Also according to DeCarlo, the Goldwaters kept him in the dark about the development of the Josie and the Pussycats cartoon show. Richard finally told him about the show the day before it premiered on TV. The cover blurb lasted until issue #47 (three issues into the Josie and the Pussycats comic book era in 1969), when it was dropped.

The Josie comic changed casts at this point to reflect the changes of the cartoon. Out went Pepper and in came Valerie (who was created by the show, not DeCarlo). Pepper was reportedly on the way out anyway, as she was becoming more of a student activist, leading the gang in “Save the World” environmental protests. John Goldwater did not like this, saying this type of character was not appropriate for Riverdale – so Pepper was gone. Albert, too, was also gone, not because the character did anything wrong, but because the elder Goldwater wanted to name a new character after a friend of his in return for favors. So hunky new band roadie (and occasional folksinger) Alan M. was created. But Goldwater’s friend didn’t want his last name used, so we never found out what Alan’s last name was (until the movie, when it was revealed as Mayberry). Sock also left the cast at this time. He wasn’t replaced, but with Pepper gone, he didn’t have much of a reason to stick around.

Enter the Pussycats

The biggest change in the comics was the introduction of the Pussycats. Once again, the real-life Josie DeCarlo was instrumental in the creation of their visual. Dan often told the story of how he and Josie attended a costume dance while on a cruise, where Josie had worn an incredibly cute handmade cat costume – complete with a tail and “ears for hats”. Thus, the kitty-costumed Pussycats were conceived. It was also DeCarlo’s idea (based on hearing his children constantly talking about rock music and bands) for the girls to become a rock band. DeCarlo also claimed that he earlier presented the idea of The Archies rock band to the Goldwaters, although he did not draw many of their early adventures (which first appeared in Life With Archie).

The creation of Josie became a well-known bone of contention between DeCarlo and Archie Comics over the years. After first hearing about the cartoon show in 1969, DeCarlo was furious over the way the Archie folks had treated him and consulted a lawyer about the situation. He was told that he would probably win a court case for creator ownership, but there certainly wouldn’t be much money involved and that he would almost certainly be fired from Archie Comics and probably blackballed in the industry. Having a family with a houseful of kids, that wasn’t really an option. Further, since his comic book work was near-anonymous, it would be tough finding work in another medium.

Later, when the Josie and the Pussycats movie was made in the early 2000s, DeCarlo actually did file suit claiming ownership. Predictably, he was fired by Archie (after working there for 43 years). He also lost the lawsuit. He had waited too long to file his claim. At least by then, his work had become much better known, and he was able to get work from people who grew up loving his work, most notably at Bongo Comics working on Simpsons comics and at DC Comics on some animated Batman-related stories. Dan DeCarlo died of a heart attack following a bout of pneumonia on December 19, 2001, at the age of 82, eight days after he lost his court case.

The original 1970 airings of Josie and the Pussycats featured a “Created by Dan DeCarlo” credit, which has subsequently been replaced on the 2007 Warner Bros. DVD collection of the original Hanna Barbera series. The new credit, quite a mouthful, reads “Created by John Goldwater and Richard Goldwater for the “Josie and the Pussycats” comic book originally designed by Dan DeCarlo”. That DVD set also features a wonderful tribute to Dan DeCarlo by friends, family, and fans, including Josie DeCarlo, Stan Lee, George Gladir (co-creator of Sabrina the Teenage Witch with DeCarlo), Bill Morrison, Mark Evanier, Scott Shaw!, Paul Dini, and others. It is marred only by this bit of legalese at the end: “The original Josie characters and characterizations were created jointly by Richard Goldwater and Dan DeCarlo. With additional creative contributions to the Josie property from Archie co-founder John Goldwater.” The 2001 live-action feature film also contains a “created by” credit for DeCarlo, again in conjunction with the Goldwaters.

For more on Dan DeCarlo, please look for Bill Morrison’s excellent The Art of Dan DeCarlo from Fantagraphic Books and the upcoming Best of Dan DeCarlo volume, featuring his Archie Comics work, coming soon from IDW. There is also a Best of Josie and the Pussycats collection from Archie Comics, featuring lots of DeCarlo’s work, but his name is mentioned nowhere in the book.

Jerry and Joe

Another real-life lady helped inspire the creation of another comic book icon. Lois Lane’s physical appearance was partially based on Jolan Kovacs, a teenage model hired by Superman creators Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel. Kovacs would later become both a professional model (working under the name of Joanne Carter) and Joanne Siegel, Jerry’s wife. Today, she represents the Siegel estate in the never-ending lawsuits over the co-creator’s rights to Superman and associated characters.

Siegel and Shuster famously (or infamously) sold their rights to Superman away early in their careers. Obviously, there’s much more to it than that, but their story has become somewhat legendary in the comics industry as a cautionary tale of what the business is capable of doing to creators. By the 1950s and 60s, the pair were largely forgotten despite their character being one of the most recognized fictional characters in history. (And despite the fact that Jerry Siegel was back at National (DC), anonymously writing stories about his character for basic page rate). It took the 1978 Superman movie and the public embarrassment of the two practically living in squalor (and hard work by Neal Adams and Jerry Robinson) to get DC to once again recognize the creators in the pages of the comics, as well as making sure the creators received an annual stipend to live on.

Amazingly, and despite the fact that literally hundreds of creators have worked on Superman stories during the character’s 70-year plus lifetime, Superman is still basically the same character that the two teenagers from Cleveland first dreamed about. Sure, his powers and backstory may now be better defined, and he may have been re-booted a time or two. But all the fundamental elements are still there – the planet Krypton, the baby in the rocket, Ma and Pa Kent, amazing powers, mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent, the Daily Planet, Lois, the S-shield. Strange visitor from another planet… Fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way! He even looks basically the same (although the physique has changed).

So, despite the fact that so many have followed and added to the legend, and despite the fact that they had help – consciously or unconsciously – from the pulps and movies and myths and even life itself – just as every creator draws something from what went before – the answer to “Who created Superman?” is pretty darn easy.

Jerry and Joe did.

Today, every time Superman appears in a DC comic, he is accompanied by the words “Superman created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.” Most of the time they are among the first words typed by every Superman writer when he or she begins a new script. Because they realize that these two gentlemen had a hand in inspiring virtually everything that came after them. They didn’t just create a hero – they created an entire genre.

KC Carlson has been working in comics since 1972, where, at the age of 16, he worked at the local magazine distributor, stripping the covers off unsold comics to return to the publishers. Since then, he has worked for DC Comics, Westfield Comics, Capital City Distribution, and many other places, continuing to destroy comics at every step.